Appearance

Chapter 5: Your Bone Bank Account

5

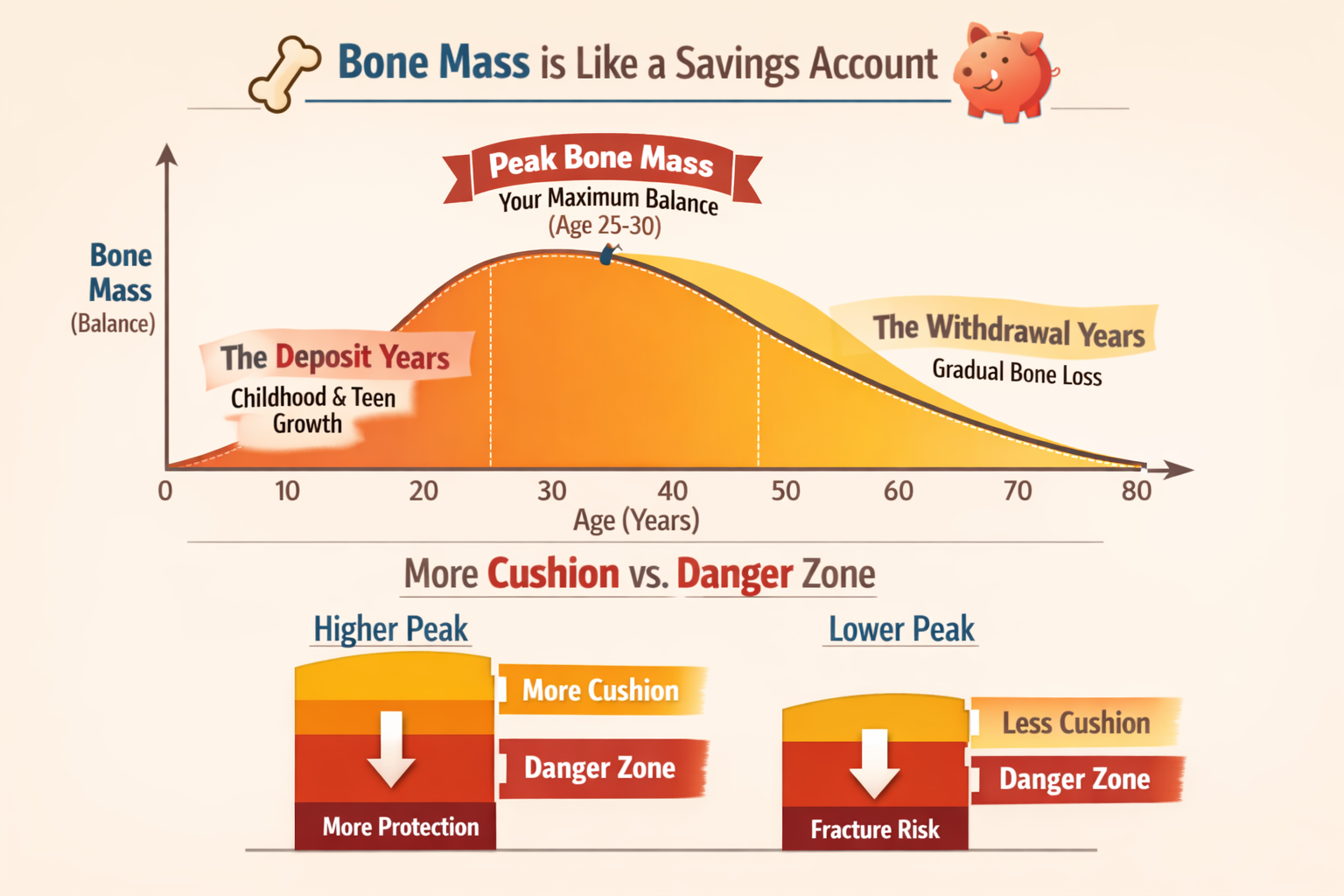

Here's something nobody tells teenagers: the bones you build before age 30 largely determine whether you'll break a hip at 80. Think of it as a retirement fund—but for your skeleton.

What Is Peak Bone Mass?

Peak bone mass is the maximum amount of bone you'll ever have. You spend your childhood and teenage years depositing into this "bone bank," and the rest of your life slowly withdrawing.

The key insight: Someone who builds a massive bone balance at 25 can afford to lose 30% and still be fine. Someone who never built much to begin with might hit the "fracture danger zone" with the same percentage loss.

When Do We Build This Bone Bank?

Here's the breakdown:

| Life Stage | What's Happening |

|---|---|

| Childhood (before puberty) | Steady deposits—about 30% of adult bone mass |

| Puberty (the golden window) | RAPID deposits—about 50% of adult bone mass |

| Late teens to mid-20s | Final deposits—the remaining 20% |

| After ~25-30 | The bank is "full"—now it's about maintaining |

The magic window: The 4-5 years around puberty are when roughly HALF of your lifetime bone mass gets built. That's ages 11-14 for girls, 13-16 for boys.

Disruptions During Puberty Have Lasting Effects

Anything that interferes with bone building during this critical window—poor nutrition, eating disorders, chronic illness, excessive exercise without enough food—can permanently compromise your skeleton.

You can partially catch up in your late teens and early 20s, but the window closes. After about 30, you can maintain bone but not significantly add to it (with rare exceptions – more on that later).

How Bones Grow During Childhood

Kids' bones grow in two ways:

Getting longer: Special growth plates (made of cartilage) add new bone, pushing the bone ends apart. When puberty hormones surge and then stabilize, these plates fuse shut—that's when you stop getting taller.

Getting wider: This is where the periosteum comes in. The periosteum is a thin but tough membrane that wraps around the outer surface of your bones (except at the joints). Think of it like a sleeve covering each bone. This membrane contains specialized bone-building cells (osteoblasts) that add new layers of bone to the outer surface—a process called periosteal apposition.

At the same time, osteoclasts remove some bone from the inner surface (the marrow cavity). The net effect: bones get wider and the inner cavity expands, creating a strong but not overly heavy structure—like a hollow tube that's stronger than a solid rod of the same weight.

Periosteal Expansion Slows Dramatically in Adulthood

Here's something crucial: the periosteum is most active during adolescence. During puberty, periosteal bone formation is in overdrive—this is when bones rapidly increase in diameter.

After skeletal maturity (early-to-mid 20s), periosteal expansion slows to a crawl. Adult bones can still add small amounts of outer bone in response to heavy mechanical loading, but nowhere near what's possible during growth.

This means: if you want wider, geometrically stronger bones, adolescence is the window. An adult can improve bone density (mineral content), but significantly increasing bone diameter is much harder. This is another reason why youth exercise is so valuable—it can permanently increase bone geometry, not just density.

Why Boys' Bones Become Wider

Here's where sex hormones make a big difference:

Testosterone directly stimulates the periosteum to add more bone to the outer surface. During puberty, boys experience a surge in testosterone that drives aggressive periosteal expansion. The result: boys' bones become noticeably wider in diameter.

Estrogen (dominant in girls) has the opposite effect on the periosteum—it actually slows down periosteal expansion while promoting bone building on the inner surfaces.

The outcome:

- Boys: Wider bones with larger outer diameter (more periosteal growth)

- Girls: Narrower bones but with thicker cortical walls (more endosteal growth)

This difference in bone geometry is a major reason why men's bones are generally stronger and more fracture-resistant—wider diameter means much greater resistance to bending and breaking forces, even if the total bone mass isn't dramatically different.

During peak growth years, kids might add 200-400 grams of bone mineral per year. Compare that to adults on the best medications, who might gain 1-3% per year. Youth is truly the time to build.

What Determines Your Peak?

Genetics (60-80%)

Your genes set the upper limit. If your parents had dense bones, you have higher potential. But genetics is just potential—you still have to realize it.

Hormones

- Sex hormones (estrogen and testosterone): Essential for the pubertal growth spurt

- Growth hormone: Drives bones to grow longer and wider

Nutrition

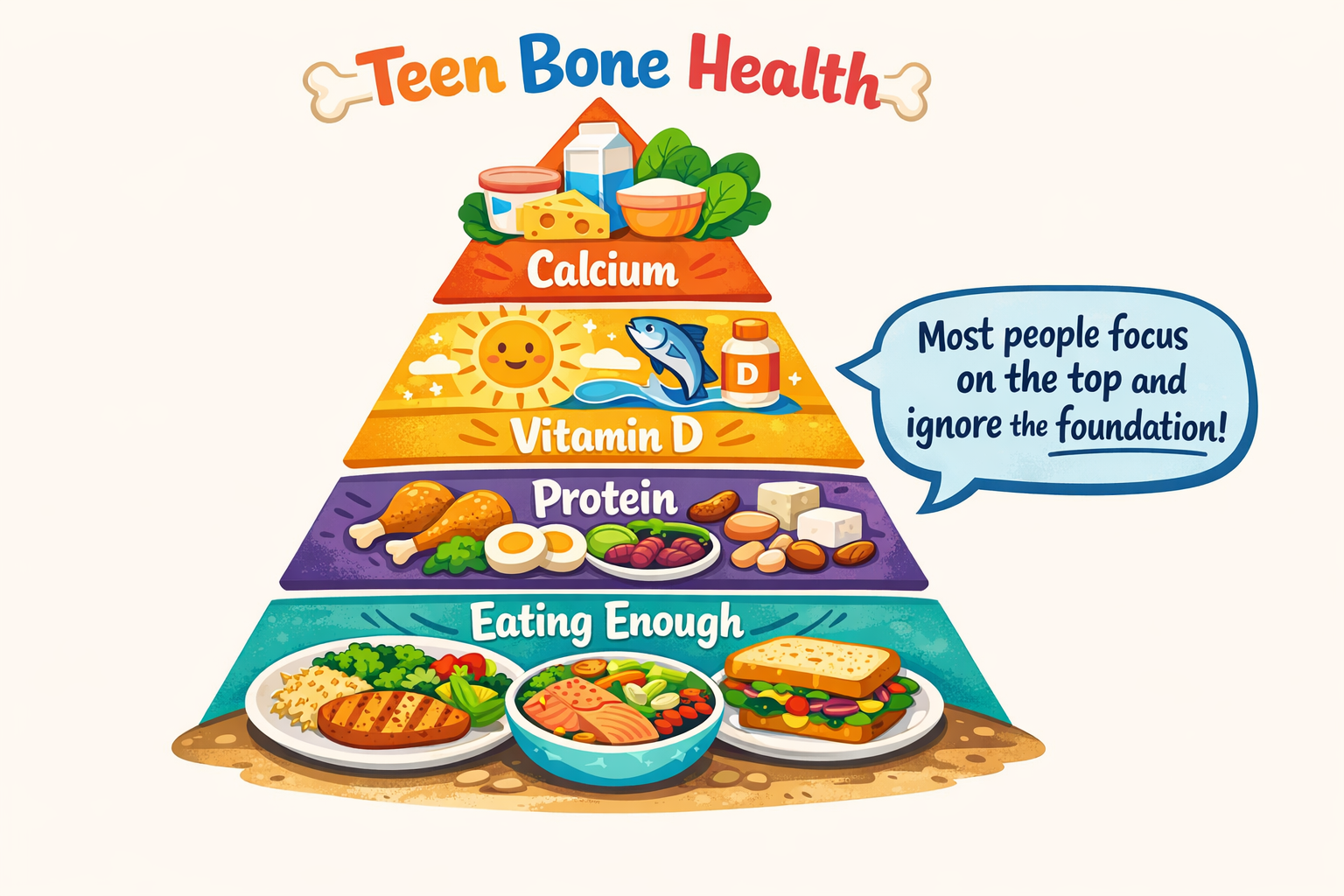

Here's what matters, in order of importance:

Enough calories: Your body won't prioritize bone building if you're not eating enough. This is THE most important nutritional factor.

Enough protein: Bones are 35% collagen (a protein). No protein = no framework to build on.

Vitamin D: Most adolescents don't get enough. Helps with calcium absorption.

Calcium: Yes, it matters—teens need about 1,300 mg daily. But it's 4th on the list, not first.

Exercise (Especially Impact!)

Bones respond to stress. When you jump, run, or land hard, your bones sense it and build stronger.

Research on young athletes shows:

- Tennis players have significantly stronger bones in their playing arm

- Gymnasts have much denser bones than non-athletes

- These benefits can last into adulthood even after stopping the sport

The skeleton adapts to the demands placed on it. This is way more effective during growth than in adulthood.

What Threatens Peak Bone Mass?

Eating Disorders

Anorexia nervosa is particularly devastating:

- Not enough calories = bone building shuts down

- Low body weight = less mechanical stress on bones

- Missing periods = no estrogen protection

- High stress hormones = accelerated breakdown

- Often happens during the critical teenage years

Recovery can help, but bone density often never fully catches up.

Too Much Exercise Without Enough Food

Athletes in many sports—distance running, gymnastics, dance, wrestling—often don't eat enough for their activity level. The result:

- Energy deficiency

- Hormones tank

- Stress fractures

- Long-term bone deficits

This affects both male and female athletes.

Chronic Illnesses

Any illness during growth can affect bones:

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Celiac disease

- Juvenile arthritis

- Cancer treatments

- Any condition requiring long-term steroids

Certain Medications

- Steroids (prednisone, etc.)

- Some seizure medications

- Some cancer treatments

Can You Catch Up Later?

The honest answer: Somewhat, but there's a deadline.

- Late teens and early 20s: Still some opportunity to build

- After mid-20s: You can maintain, but not significantly add

- Lost peak bone mass = starting the age-related decline from a lower point

The earlier any problem is addressed, the better the outcome.

Why This Matters for Public Health

Here's a striking statistic: A 10% increase in peak bone mass could delay osteoporosis by 13 years.

Prevention during youth is far more effective than treatment in old age. Yet most bone health attention goes to elderly people, not teenagers.

If you have teens in your life, the best things you can support:

- Eating ENOUGH (especially if they're active)

- Getting protein at every meal

- Some vitamin D (supplements often needed)

- Impact activities—jumping, running, sports

- Healthy body image (eating disorders are bone destroyers)

The Bottom Line

The bones you build by age 30 are the bones you'll live with. The teenage years are the golden window—use them wisely.

Key takeaways:

- Peak bone mass is like a retirement account for your skeleton

- About 50% is built during the 4-5 years around puberty

- Genetics sets potential; nutrition and exercise determine if you reach it

- Eating enough matters MORE than specific supplements

- Disruptions during growth have lasting consequences

- The window to build closes in your mid-to-late 20s

Next up: we'll explore why men's and women's bones are so different—and why this matters for bone health.